Here is the skinny on back pain.

But this is an overview of the more common causes of back pain. There are indeed many less common causes –sometimes even tumors – so if you read this and if you have persistent and worsening back pain, it is always best to consult with your doctor.

In my practice, I see three main causes of back pain:

- Muscular Sprains

- Disc Herniations

- Arthritic Degeneration

I will discuss each of these, but less common causes include fractures, tumors, inflammatory diseases like Rheumatoid Arthritis, urine infections, scoliosis, and many others. Tumors are very rare, so if your back pain does not improve, don’t assume that you have cancer. But, by the same token, go to a doctor to get it examined.

ANATOMY

The spine is made up of individual vertebra. There are 24 in all: seven in the neck(cervical region);twelve in the mid spine(dorsal region ); and usually five in the lower back (lumbar region). See diagram below. The purpose of each vertebra is to provide overall support, but also to protect the spinal cord and nerves. The cord is held within the ring at the rear of each vertebral body and the nerves exit through an opening called a foramen.

If the spine was instead only one long column with a canal in the rear to hold the spinal cord, it might look like a bamboo pole. This type of construct would serve the above two functions of support and protection, but obviously, one would not be able to bend. Therefore, the 24 individual segments allow for mobility. In this respect, a cushion is in between each vertebra and this cushion is called a disc. While a slight degree of mobility is allowed between, say, three vertebra, the sum degree of total motion is large – distributed among the entire spine.

The discs also allow for stability and shock absorption between the vertebral bodies. Also holding, all of the vertebra together in a long, segmented column are multiple ligaments and muscles.

Finally, the spinal cord is an extension of the brain and is a complex network of nerves extending to the trunk and limbs. Nerve roots branch away from the cord at all levels( the first two cervical levels are labeled C1-2; the first two lumbar levels are L1-2; and so forth.). The actual spinal cord ends at the L1-2 level and forms a tail of nerves known as the cauda equine, which continues to exit at the lower lumbar levels.

MUSCLE SPRAINS

Muscles, as well as ligaments which surround the spine can be sprained or strained. Depending on one’s age or the shape that they are in, the sprain can even occur with a relatively minor incident like bending, twisting, or even sneezing. I personally have thrown out my back from coughing.

Usually, the pain is confined to the back and does not radiate down into the legs (sciatica). Likewise, there is no numbness, tingling, or weakness. A neck sprain will not result in burning pain into the arms, unless a pinched nerve is involved –either from a disc herniation or from a stretch injury.

Treatment usually consists of rest and restricted activity; medicine such as anti-inflammatories and muscle relaxants; sometimes physical therapy; or even a corset brace.

Usually a sprain will resolve within 1-3 weeks. Spinal exercises may prevent recurrences.

DISC HERNIATIONS

The disc is a circular, checker –like cushion that lies between each vertebral body. It consists of a firm outer rim-the annulus and an inner gelatinous core-the nucleus pulposus. When the annulus tears the nucleus pushes out and frequently into the spinal cord or an exiting nerve root. This is known in lay terms as a slipped disc. I compare the disc to a jelly doughnut. Squeeze the doughnut and the jelly will squirt out. Or think of a tube of toothpaste. Squeeze it and the toothpaste pushes out. This is a rough analogy as the nucleus is thicker jelly-like sap on a tree.

A slight disc displacement of the nucleus is referred to a bulge or a protrusion. A more serious displacement is called a herniation. When the nucleus completely displaces out and into a nerve –like toothpaste onto the counter- it is called an extrusion: obviously more serious.

Patients with a disc herniation may only have local back pain, but frequently also have intense pain which radiates down an arm or leg. We call this radiculitis. In the lower extremities, it is referred to as Sciatica. This pain pattern frequently extends from the back towards the buttocks and down the back of the thing. A more severe disc herniation can cause numbness and tingling or even weakness.

Sometimes patients have only sciatic pain but no back pain. When I tell them that the source of their pain is in their back, they are commonly baffled. “But, my back feels fine!” But nerves in the spinal cord are like electrical wires. A disc hitting a nerve in the lower lumbar spine may alter feeling in the foot if that nerve supplies feeling to the foot. So back pain may not occur. It’s no different in your home. When the lights go off in the bedroom, the problem could be in the fusebox in the basement-not the bedroom.

Treatment –if a disc is a minor bulge –is similar to a back sprain:rest,medicine,therapy.

X-rays may be needed, but the disc can only be seen on a special study like an MRI or CT scan.

A more severe herniation or extrusion may require surgery to remove the fragment. The entire disc is not removed. Many patients-even with herniations–recover with rest and time and do not necessarily need surgery. Sometimes, an epidural cortisone injection into the spine might successfully work and negate the need for surgery. These are more commonly being performed nowadays.

While I have seen many successful results of disc surgery, I have also observed countless patients who have had discs surgically removed who have not done well and have developed chronic back pain—sometimes even after repeat operations. Therefore, I encourage my patients to first try a more conservative approach and many will successfully avoid surgery. Therefore, one should not rush into back surgery.

Most disc surgery is elective. It becomes more urgent if a severe nerve injury occurs. For example, severe weakness of the shoulder or ankle. A foot drop. Or, diffuse and complete loss of feeling -not merely pins and needles or a tinglingsensation. A reason for emergency surgery would be the rare occurrence of bowel or bladder incontinence. Each case must be individually accessed.

One final word about the new trend towards total disc replacements: BEWARE!

These are not hip or knee replacements –not even close. They are new and have not stood the test of time. Those who advocate doing them have not addressed the simple question of how to remove the devices or revise them if they fail—as they certainly will over time. And, what if they displace into the spinal cord or into a major blood vessel like the aorta ? Disaster !!

ARTHRITIC DEGENERATION

The spine ages-like every other body part. Older individuals develop arthritis of the facet joints which allow some spinal gliding motion. The disc loses water content and dries up and shrinks to some extent. The chairman of my training program used to compare the disc in a youngster to a juicy grape and the disc in an older person to a raisin. This is partly why people lose height as they age. Another reason is due to osteoporosis which can cause the vertebral body to crush and collapse.

With arthritis, bony spurs also form and these can press on a nerve root. The combination of a dried up disc and spurs and vertebral collapse can impinge on the cord or nerve roots-thus causing a similar effect as a freshly herniated disc in a younger person. Natural overgrowth of bone-spinal stenosis- can further squeeze the cord in the spinal canal, causing pain or neurological symptoms.

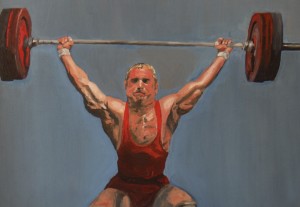

Many of these changes can occur in younger people-especially in people who do heavy labor. Many develop what is called degenerative disc disease. The disc deteriorates and prematurely becomes a raisin. It can become more prone to herniated.

The work-up and initial treatment is the same as discussed under disc herniations. An MRI may be necessary. Epidurals may help relieve pain.

The last resort is surgery. Today, most spine surgeons recommend removal of the degenerated disc along with a fusion of one or of several spinal levels to remove localized motion which can produce pain. The fusion is supplemented with metal instrumentation: screws, rods, cages, etc. The results are usually very good in the neck. The results of fusion with instrumentation in the lumbar region are not as good –at least the results that I have seen in many patients.

( I do not perform this surgery.) If I told you that the results that I have seen are 50/50, I would be generous.

Too often patients tell me that they are going to have this surgery because they cannot live with their back pain and ”what else can I do?” So they have a fusion with instrumentation and frequently still are no better. And, sometimes they are advised to have yet another operation to either remove the hardware or refuse another level-not uncommonly with equally unsatisfactory results.

I am not a big fan of this surgery –as you can see. I would advise a potential candidate to try and try more conservative measures and not rush into this surgery. And again, stay away from a disc replacement.

One procedure that does frequently work is a simple laminectomy to remove overgrown bone for spinal stenosis. If this procedure is kept simple without metal instrumentation or a fusion, the results can be night and day and very pleasing.

Please note: these articles are for general information. They are not intended to serve as medical advice or treatment for a specific problem. Diagnosis and treatment of a problem can only be accomplished in person by a qualified physician.